Is Plant Protein Inferior? The Truth About Leucine and Muscle Growth

Why Vegetarians and Vegans Can Get Great Gains

TLDR: While plant protein is often labeled as inferior due to its lower leucine content and slower digestibility compared to animal sources, it is just as effective for muscle growth when properly managed. Because leucine acts as the primary chemical trigger for muscle protein synthesis, plant-based athletes simply need to consume a higher total volume of protein or blend different sources—such as pea and rice—to reach the necessary leucine threshold and complete their amino acid profiles. Ultimately, the body does not distinguish between protein sources once they are broken down; as long as you meet your daily leucine and essential amino acid requirements, plant proteins can produce identical results in strength and hypertrophy to animal-based diets.

The "meathead" stereotype is slowly evolving. For decades, the image of muscle-building was inseparable from chicken breasts, tuna cans, and whey shakes. If you told someone you were chasing a 300-pound bench press on a plant-based diet, you’d likely be met with a skeptical look and the inevitable question: “But where do you get your protein?”

It is time to retire the myth that plant

protein is "inferior." By examining the tension between mechanistic efficiency and clinical outcomes, we can build a roadmap for the successful plant-based athlete. To understand how to optimize plant-based gains, we must look at two leading, yet seemingly opposing, evidence-based perspectives.

The Efficiency Argument: Dr. Gabrielle Lyon

Dr. Gabrielle Lyon, a proponent of "Muscle-Centric Medicine," argues that while plant-based gains are possible, they are less efficient due to three main factors:

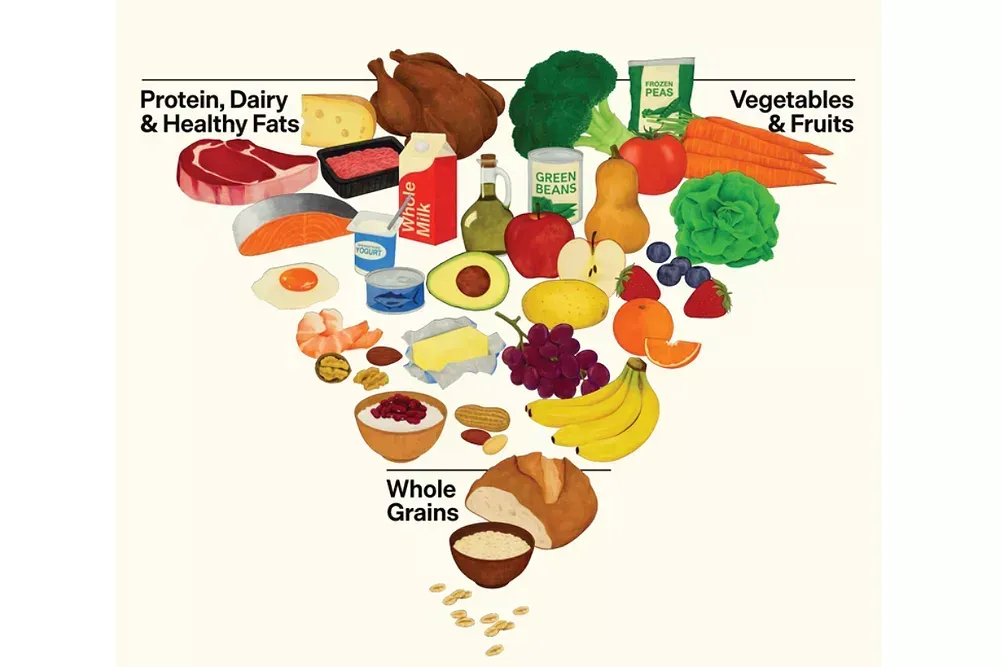

- The Leucine Threshold: Muscle Protein Synthesis (MPS) requires 2.5-3g of leucine per meal. Animal proteins hit this easily, whereas plant sources often require larger volumes of food to "flip the switch."

- Bioavailability: "Antinutrients" in plants (like fiber and phytates) can reduce protein absorption to 60-80%, meaning 30g of bean protein doesn't equal 30g of absorbed protein.

- The Caloric Tax: To get 30g of protein, you might eat 200 calories of steak versus 1,100 calories of quinoa. This makes staying lean while bulking more difficult on whole-plant foods.

My initial response to Dr. Lyon is to point out that one could use plant-based isolates (like pea protein) and strategic food pairing to hit leucine targets without the caloric bloat. Additionally, some plant sources are great sources of protein. Let’s take a closer look at a counterargument.

The Big-Picture Rebuttal: Dr. Idz

Evidence-based physician Dr. Idz (Idrees Mughal) counters that mechanistic "triggers" matter less than long-term outcomes:

- Results vs. Theory: Clinical trials show that when total protein and calories are matched, there is no significant difference in actual muscle growth between plant and animal groups over time.

- The Health Tax: Dr. Idz highlights that animal proteins often come with a "health tax." Swapping to plant sources is linked to lower LDL cholesterol and ApoB (heart disease risk), reduced inflammation, and better longevity.

- Daily Totals Over Per-Meal Precision: While critics obsess over "wasted" anabolic windows, Dr. Idz asserts that total daily protein intake is the primary driver of growth for most people.

Dr. Lyon focuses on the potency of the anabolic trigger; Dr. Idz focuses on total outcomes and cardiovascular health. For the modern athlete, the path is clear: prioritize total protein, use isolates for efficiency (if needed), and enjoy the long-term health perks of a plant-forward lifestyle.

Optimization vs. Outcomes: A Comparative Analysis

The primary tension here lies in how we measure success. Dr. Lyon views the body as a machine requiring a precise trigger; Dr. Idz views it as a resilient system driven by total nutrient availability.

This synthesis suggests that while we should be mindful of meal quality (micro-level), we have immense flexibility if we hit our daily targets (macro-level). In fact, the "barriers" Lyon mentions—fiber and phytates—are the same components Idz credits for preventing cardiovascular disease.

To bridge this gap, a plant-based athlete can simply implement the 10% buffer: by eating slightly more total protein, you overcome absorption issues while retaining the cardiovascular benefits.

Furthermore, we can eliminate the "caloric tax" by using plant-based isolates. By stripping away the starch from peas or soy to create a powder, you optimize the protein profile—achieving high density and high leucine—without the associated health risks of animal fats. Even issues like sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) can be managed by mixing plant sources and strategic supplementation.

Final Thoughts

The conflict between physiological optimization and practical health outcomes isn't a zero-sum game; these are complementary layers of a sophisticated training strategy.

Dr. Lyon’s research informs us of the important consideration for the protein quality of each meal. Dr. Idz provides the big picture, demonstrating that athletes can perform effectively across various sources. By synthesizing these views, we find that the "weaknesses" of plant protein are merely manageable variables.

Muscle is fundamentally "nitrogen-blind." It does not care if its amino acids come from a cow or a kidney bean, provided the requisite materials are present. By adopting a "muscle-centric" approach to plants—prioritizing protein density, utilizing isolates where efficiency is required, and aiming for a slightly higher daily total—you achieve the "holy grail" of fitness: the high-performance physique of an athlete with the internal health markers of a longevity-focused lifestyle.

Ultimately, your gains are determined by the intensity of your training and the consistency of your nutrition. If you hit your targets, the gains will follow.