Is a Calorie a Calorie?

Understanding the Nuances of Energy Balance

TL; DR: While the first law of thermodynamics (Calories In vs. Calories Out) remains the fundamental baseline for weight change, this article explores why the "a calorie is a calorie" mantra is an oversimplification. From a holistic and physiological perspective, the source of the calorie matters for body composition and long-term health. Factors like the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF)—where protein requires more energy to digest than fats or carbs—and how different macronutrients impact hormones (like insulin), satiety, and energy levels mean that 2,000 calories of whole foods will produce vastly different results for your metabolism and hunger than 2,000 calories of ultra-processed snacks.

Is a calorie a calorie? This question typically has to do with the standard understanding of energy balance. For instance, if you want to lose weight, then you need to maintain a calorie deficit. If you wish to gain weight, then you need a calorie surplus. This is based on the first law of thermodynamics, which states that energy or matter is neither created nor destroyed, but merely changes form. This implies that what matters is not the macronutrient distribution of your diet, but the overall balance of energy expenditure versus energy consumed, i.e., if you expend more than you consume, you will lose weight or if you consume more than you expend, then you will gain weight.

Unfortunately, there are two dogmas that have to do with this fundamental principle of physics. The first wants to deny that weight management boils down to energy balance. They operate under the (consciously held or not) assumption that something can come from nothing, i.e, energy can be created from nothing or annihilated into nothing. The other dogma is that weight management is

merely a matter of energy balance, i.e., struggling with weight management is a personal failing that needs to be overcome with discipline.

I argue that both dogmas are incorrect. In other words, while weight management ultimately boils down to energy balance, there is a lot that goes into that balance on both the energy expenditure and consumption sides of the equation, including biological, psychological, and social factors. Let’s use carbohydrates as an example.

Do Carbs Make You Gain Weight?

Do carbs make you gain weight? The short answer may depend on the ratio of energy consumed to energy expended. Are the carbs pushing you over the edge into more energy consumed than expended? Sure, they do contribute to weight gain in this case, but it isn’t the kind of macronutrient it is as much as it is the fact that it’s just more energy consumed. In other words, you wouldn’t be gaining weight by virtue of the fact that the macronutrient is a carbohydrate, you would gain weight because it’s adding more calories to the energy consumed side of the equation.

I recently posted the following comment on one of my social media pages:

“This is your friendly reminder that carbs do not make you gain weight. Being in a caloric surplus makes you gain weight.”

I got a few responses to this, including an accusation that I did not understand “metabolic nutritional health” and an assertion that a calorie is not a calorie.

The simple fact of the matter is that a calorie is a calorie and that carbohydrates are not especially “bad" when it comes to weight management. For those who need references, please seeHill and colleagues (2013),

Hall et al (2012), and

Frank et al (2018) for more information on this point and for what I am going to argue shortly.

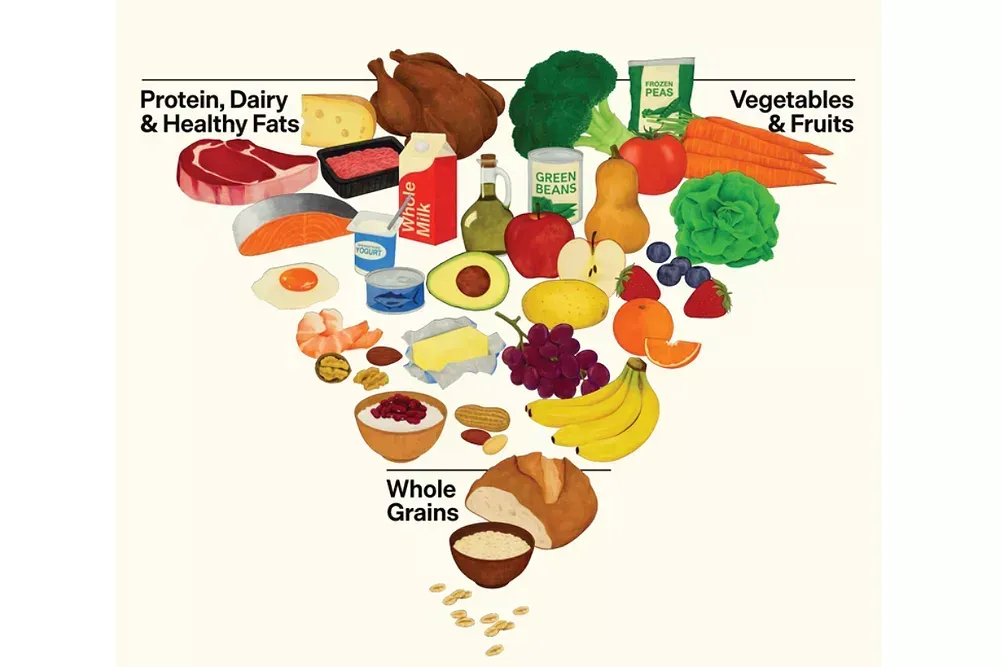

If carbohydrates by virtue of being carbohydrates do not make you gain weight, why do people on high-protein and low carb diets generally have an easier time losing weight? First, as the first law of thermodynamics implies and as the research suggests, the macronutrient content of a diet does not matter so long as calories are controlled for. In other words, you can lose weight on any diet so long as you maintain an energy deficit. The reason why someone on a high protein diet might have an easier time has to do with the fact that protein both promotes satiety better and requires more energy to digest than the other macronutrients.

Does this mean you should eliminate carbs altogether if you want to attain the greatest amount of weight loss? Definitely not. Why? Because of fiber. If you read my fiber guide, then you know that if any food can be called a “superfood”, it’s fiber. Fiber provides many benefits including promoting digestive health, heart health, gut health, decreasing cancer risk, etc. For the context of this argument, it is also highly beneficial for weight management because high-fiber foods tend to be more filling than low-fiber foods. The bulk provided by fiber can help you feel satisfied for longer, potentially reducing overall calorie intake (seeJovanovski and colleagues, 2020, as an example).

One important fact worth noting is that fiber is a carbohydrate, or more specifically, a non-digestible carbohydrate. So it is not only the case that carbohydrates do not necessarily make you gain weight, certain kinds can actually help you lose weight.

The Limits of Discipline

What about the other dogma? Do people who struggle with weight management simply lack discipline? While I agree that people often lack the discipline required to achieve their goals, the amount of discipline required is not evenly distributed. Weight management simply comes easier to some people than it does to others due to genetic, hormonal, psychological, and socioeconomic differences. For example, two people of similar height and weight can have significantly different resting metabolic rates (due to genetics and/or hormones) and even if they do have the same resting metabolic rate, they may not have equal access totime and/or resources.

In “The Social Determinants of Health and Fitness”, I wrote about how Holistic Training advocates for a comprehensive view of well-being, recognizing that health and fitness are not solely individual acheivements but are deeply shaped by social determinants. These includesocioeconomic status, education, and access to resources, which impact

food choices, exercise opportunities, and

health literacy. Furthermore, your

physical

environment, like safe parks and

walkable streets, and your

social connections providing

support and motivation, are crucial for fostering a healthy lifestyle. By understanding these interconnected factors, individuals can find adaptable solutions and work towards a more balanced and fulfilling life.

While social factors may make things easier or harder depending on who you are, what about motivation and discipline as factors? First, I will define what I mean by motivation and discipline. Motivation can be considered the “why” behind your actions. It is the internal or external drive that inspires you to start something, pursue a goal, or make a change. It can be powerful at the outset but is often fleeting and can fluctuate based on feelings, circumstances, and energy levels.

Discipline is the “how” of your actions. It’s the ability to train yourself to behave and work in a controlled and regular way, to pursue something consistently regardless of how you feel (thus differentiating itself from motivation which is highly dependent on how you feel). It’s about adherence to a chosen course of action, even when motivation is low or absent.

How much are motivation and discipline genetically determined? Motivation and discipline, like many complex human traits, are generally understood to be influenced by a combination of genetic predispositions and environmental factors. They are not solely determined by genes, nor are they purely a product of upbringing and experience. That being said, astudy by Kovas et al (2015) found that among 13,000 twins aged 9-16, “genetic factors explained approximately 40% of the variance and all of the observed twins’ similarity in academic motivation.” The results of this study are particularly compelling not just due to the large sample size, but also due to the cross-cultural reliability of the results (the subjects were from a variety of countries across the world). This is supported by

Malanchini and colleagues (2025), who explain that twin research suggests that “genetic differences between people contribute to their differences in non-cognitive skills…academic motivation, self-regulation, and personality, are moderately heritable (~30-50%).”

Discipline, like motivation, is influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Let’s consider the heritability of related traits. First, self-control, a key component of discipline, is up to 60% heritable according to ameta-analysis by Willems et al (2019). Conscientiousness, another core component of discipline, includes characteristics like organization, diligence, and responsibility and is significantly determined by genetics according to

Luciano and colleagues (2006).

Researchers have also studied perseverance and grit. For instance,Rimfeld et al (2016) found that “grit perseverance was substantially correlated with…conscientiousness” and that it is significantly influenced by genetic factors with a heritability estimate of 37%.

By now it should be clear that both motivation and discipline are products of gene-environment interactions with genetics playing a significant role. It should go without saying that one has no control over their genetics, nor do they have any control over who they are born to and under what circumstances. They certainly have very little control over their upbringing and overall environments in some of the most formative years of their lives. Even as independent adults, there are many environmental factors that are partially or completely outside of our control. Hence my point about the unequal distribution of discipline and how much it is required.

The Middle Way

Now that I have thoroughly discredited these two dogmas about calories and weight management, what is a more helpful understanding? The answer lies somewhere in the middle. While a calorie is a calorie and weight management ultimately boils down to managing energy balance, the many factors that go into that make it much more complicated than a mere matter of will and discipline. The fact that so much is outside of our control–and what is within our control is still outside of it to a significant extent–does not imply that nothing can be done. I certainly wouldn’t bother being a coach if I thought that.

There are individual constraints that I can work with that can help individuals improve themselves and their situations. Doing so most effectively requires an understanding of the biological, psychological, and social factors at play. Thus, if a client wants help losing weight, I ultimately have to help them manage a calorie deficit, but the way I go about doing it most effectively and sustainably must be informed by their specific constraints. Some clients may need more support than others and that support can look like me helping them cultivate the motivation and discipline necessary for them to achieve their goals. Others may simply need information and guidance. Long story short, I cannot treat everyone the same and I must work with what we have as coach and client. I cannot do that as effectively if I ignore the social determinants of health and fitness as well as biological and psychological factors.

Final Thoughts

This post addresses two common dogmas surrounding weight management: that energy balance doesn't matter, and that weight struggles are solely a matter of discipline. I argue that both are incorrect, proposing a middle way where weight management fundamentally relies on energy balance (calories in vs. calories out), but acknowledges the profound influence of biological, psychological, and social factors on both energy consumption and expenditure. I clarify that "a calorie is a calorie," and use carbohydrates as an example. Furthermore, I delve into the limitations of solely relying on discipline, explaining that both motivation and discipline are significantly influenced by genetic predispositions, as well as environmental factors. Social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status, education, access to resources, physical environment, and social connections, are also crucial, creating unequal playing fields for individuals trying to manage their weight.

While weight management ultimately adheres to the laws of energy balance, achieving and maintaining that balance is far more complex than a simple matter of willpower. It is deeply intertwined with an individual's unique biological makeup (including genetic predispositions for traits like motivation and discipline), psychological factors, and the broader social and environmental contexts they inhabit. Therefore, effective and sustainable weight management requires a holistic approach that recognizes and addresses these multifaceted individual constraints and external influences, moving beyond simplistic "eat less, move more" advice or blaming individuals for perceived lack of discipline.